Student Buy-in and Student Resistance

Written by: Dr. Christine von Renesse and Dr. Philip DeOrsey (see image).

We use inquiry in all our classes, in particular in our mathematics for liberal arts (MLA) classes. In our typical MLA class, students work in groups on mathematical explorations, and then share out their thinking in whole class discussions .

Student Resistance

Unfortunately, teaching with active learning strategies like inquiry-based learning (IBL) often leads to student resistance. “Felder and Brent (1996) note that enthusiasts of student-centered or learner-centered instruction are in for a ‘rude shock’ […] when they begin to actually implement updated pedagogies in their classroom.“ (Tolman, page 2. See references below.)

Tolman defines student resistance as “an outcome, a motivational state in which students reject learning opportunities due to systemic factors.” They further go on to state that “resistance is a motivational ‘state’ and an outcome of multiple interacting factors; it is not a ‘trait’ that endures over time or exists as part of a student’s personality or genetics.”

If you have facilitated an active learning classroom you may have experienced some of the following from your students:

- Unwilling to engage in any task (anxiously or passive aggressively).

- Openly rejecting tasks: “Why do I have to do this? When do I ever use this?”

- Aggressive when questioned about their reasoning. “This is the correct answer, who cares how I got there?”

- Acting helpless: “I can’t do this!”

- Demanding different teaching style: “You are not teaching us!”

Sound familiar? Which student behaviors, if any, have you encountered that fall under “student resistance?” Do you understand why your students behaved the way they did?

To make inquiry-based learning work we want to lower student resistance, but to do this we first need to understand student resistance more deeply. One great resource is Tolman’s book “Why Students resist learning: A practical model for understanding and helping students”. He uses the Integrated Model of Student Resistance (IMSR) to explain how metacognition, cognitive development, negative classroom experiences, and environmental forces (work, family, culture/racism, disabilities) influence student resistance. It is tempting to think that student behavior only results from our facilitation during class but that is rarely the case. Seeing all the reasons that may lead students to resist can help us understand students’ feelings and behaviors and help overcome resistance.

Tolman explains that students either act to “preserve self” or to “assert autonomy”, and that they can do so actively or passively. It is helpful to understand that an expression of frustration can really mean that a student needs to assert autonomy, or that a student that seems afraid and reluctant to work is possibly trying to protect themselves from failure and humiliation. The more we, the facilitators, understand about why students resist the better we can support them in choosing to instead engage in learning again.

Makira [page 45] claims that “despite all of the literature-based evidence pointing to the importance of student–faculty interaction in college, many faculty overlook, or underestimate, the impact they have on their students. There is often a tendency for faculty to assume that talent and hard work alone will get students through the course, when in reality many other factors—including their own behavior toward students—can play important roles. In their study, the three variables that correlated to positive student outcomes (comprising the student–faculty relationship factor) were the student looking up to the professor, feeling comfortable approaching the professor, and feeling that the professor respects the students.”

Similarly, Tolman writes that “Communication theorists have also revealed some important ways that professor-student relationships shape learning and resistance. In this literature, immediacy refers to the amount of interpersonal warmth and social connection that an instructor demonstrates toward students.” [...] By understanding that sometimes students may be reacting to our own misbehaviors, including not adequately preparing students for tasks or not helping them understand the reasons for assignments[...], we may discover opportunities to alter our behavior to enhance student learning. By understanding the important role that immediacy plays in fanning or damping student resistance, we can seek to develop our social connection with students.” (Tolman, page 10)

When student buy-in is missing, e.g. resistance is up and students are blaming the facilitator, it is tempting for the facilitator to blame students - instead of looking for solutions to the problem. This can lead to a vicious cycle in which learning becomes harder and harder.

Student Buy-In

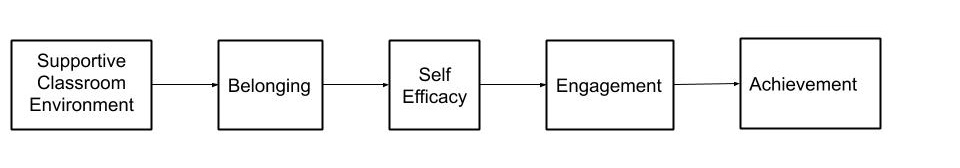

Zumbrunn et al. provide an interesting perspective in their study showing that belonging plays a crucial role for students’ engagement and achievement. Belonging is defined as the extent to which students feel accepted and supported by teachers and peers. They “argue that a supportive classroom environment predicts belonging and that belonging likely predicts self-efficacy and task value [value beliefs for learning tasks]. These motivational beliefs, in turn, independently predict engagement and engagement predicts achievement.”

This implies that for learning to be possible we as facilitators need to create a supportive classroom environment so that students feel that they belong. There are some strategies available on how to get students to buy-into their college classes, for example Dana Ernst' blog about setting the stage in mathematics and Tolman's book (more general), but successfully getting buy-in seems to depend on many factors, such as facilitator behavior, beliefs, and personality.

(Some of) Our strategies for Student Buy-In:

We describe ten general strategies that we use to encourage student buy-in. We relate each of these strategies to the revised model of classroom support for motivation as described in [Zumbrunn]. These connections are noted in parentheses for each strategy. Not all strategies listed are employed by us both, but we chose to list them jointly. You can see it as a menu to choose from, with probably many more good ideas missing.

- Early success (belonging and/or task value)

Facilitators make sure that all students experience success early in the semester. To this end we choose shorter activities in the beginning - with an especially low threshold - that we know to be doable for everyone. In our experience if students fail to find early success they can quickly feel like they do not belong in the class.

- Reflection (self-efficacy)

Students watch short video clips or movies (e.g. The Proof) and write journals 2-3 times during the semester. Topics range from math-autobiographies, growth mindset, mind set and physiology, productive failure in presentations, making mistakes, persistence, (lack of) diversity in mathematics, injustice in mathematics, to applications of mathematics.

- Trust (supportive classroom and belonging leading to self-efficacy)

As facilitators we truly believe that all students can be successful and make sure to tell them repeatedly that we believe in them and trust them. You can find some more ideas related to trust and the first class of the semester in this blog.

- Positivity (supportive classroom)

As facilitators we stay positive during class, especially when our students make negative comments or show other forms of resistance to our class environment. It also helps to regularly show students cool things in mathematics.

- Immediacy (supportive classroom and belonging)

In order to show our immediacy we often come to class early to sit with students and ask them questions beyond the classroom (“How are you doing? How are your other classes? How is your family? Do you have plans for break?” …). We make sure to tell them some stories about ourselves as well. The idea is to create a personal connection and to show students that we care about them as people.

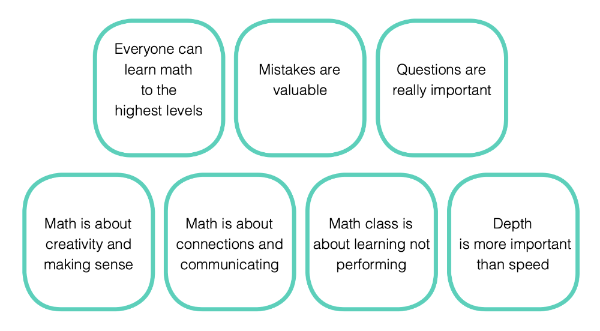

- Classroom Norms (supportive classroom and belonging)

In group and class discussions, we generate norms for our classroom community. These norms can include beliefs about mathematics, for example “Mistakes are valuable”, but they can also include how we want students and facilitator to act in class, for example: “Acknowledge the difference between intent and impact.” We like the Anti-Oppressive Resource for Establishing Norms for Discussion and Jo Boaler's Resource for Norms in a K-12 Mathematics Classroom.

- Community Building (supportive classroom and belonging)

We consciously work on building a class community in the beginning of the semester. For example, we regularly change the grouping of students to make sure that all students know each other. Grouping students according to needs later on can be helpful as well.

- Engagement

To help students stay engaged we make sure to provide activities that allow all students to work at their learning edge.

- Belonging and Equity

We also specifically support student minorities, making explicit that we welcome all students and do not accept any microaggressions. We suggest this for example this resource.

- Art (Achievement)

Most students appreciate some form of art. Connecting mathematics to creating art is a powerful tool to motivate students. If students already know how to create art it is likely that they will enjoy this. If not, the promise of being able to is enticing. Of course you can choose any other form of achievement for this section, for example an applied project for a calculus class.

As a follow up to this more theoretical blog, we suggest reading the following...

References:

Cavanagh, A. J. et al. 2017. Student Buy-In to Active Learning in a College Science Course. Cbe Life Sciences Education. 15(4). 15:ar76, 1–9.

Makira, M., Pasos, P. 2012. Connecting to the Professor: Impact of the Student–Faculty Relationship in a Highly Challenging Course. College Teaching, 60: 41–47.

Tolman, A. O., J. Kremling (Eds). 2017. Why Students resist learning: A practical model for understanding and helping students. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Zumbrunn, S., C. McKim, E. Buhs, L. R. Hawley. 2014. Support, belonging, motivation, and engagement in the college classroom: A mixed method study. Instructional Science. 42(5). 661-684.