Routines for Reasoning: A Journey of Bravery and Mathematical Thinking

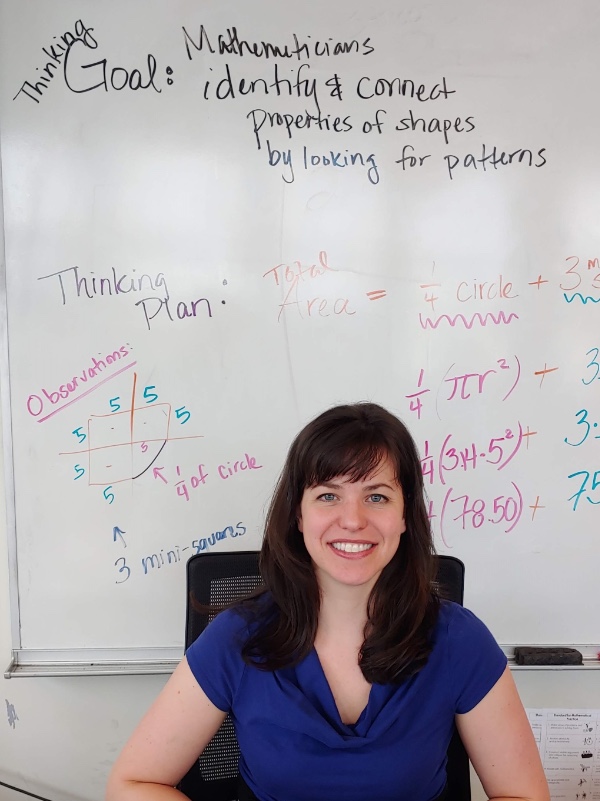

Written by: Elizabeth Azinheira, 7th Grade Teacher at Forest Park Middle School in Springfield.

In this blog, Elizabeth Azinheira describes how reading the book "Routines for Reasoning" and implementing the ideas has changed her teaching. In her intervention classroom, Liz carefully designs lessons that allow all her students to work at their learning edges. This may include working on language skills as well as working on mathematical ideas from lower grade levels. Liz was supported in making these changes by Dr. Christine von Renesse in a graduate course by special arrangement which included weekly video meetings and several classroom observations. After telling her personal story, Liz provides an overview of the routines and makes some of her lesson plans available for others to use.

The Journey...

Upon being given their own classroom, every teacher quickly learns that the reality of teaching is very unlike the experience they imagined. After all, the image conjured in the imagination of an unsuspecting would-be teacher is likely that of a classroom filled with obedient children who are ready to receive information from the wise and knowledgeable teacher, who stands at the front of the classroom and tells them what to do. “What could be more gratifying than dispensing valuable information to young hearts and minds?” one might think. “How could any child refuse the gifts of knowledge and wisdom I so obviously have to bestow upon them? Surely they would recognize the value of what I have to say.” I’m pretty sure we’ve all had some version of this daydream.

Cue the sound of a scratched record. (Do my fellow millennials even get this reference? To the Gen-Zers entering the workforce, you should know that, before MP3s and streaming there was this thing called a CD, before which there were tapes, and before those there were records and those records created a dramatic ripping sound when scratched and – alas, I digress. Let me get back to the topic on hand).

No, no, lovely would-be teacher. The reality of teaching today is that you will be simultaneously (take a deep breath now): (1) assessing student’s prior knowledge while teaching them the current standard but also considering how your instruction will affect students’ understanding and subsequent mastery of the next standard; (2) meeting the (often conflicting) demands of administration while (3) managing the unimaginably creative array of conflicts between students whose social skills are -ahem – developing; (4) communicating with parents of varying interest, expectations, and influence; (5) planning instruction for the average student, the advanced student, the student with learning difficulties, the student with major gaps in prior knowledge, the student with limited English proficiency, and –lest we forget—the student, who, for some reason (and unbeknownst to you, despite your infinite attempts to understand) does not like you and makes your job very difficult. Then, after making roughly 1,500 in-the-moment, on-the-fly, and gosh-I-really-hope-I-just-made-the-right-choice decisions of just one single day, you have the pleasure of doing it all over again the next day. (Whew!)

And yet, here’s the thing: It. Is. Awesome. The best ride you’ll ever be on. Worth every moment of struggle, every extra sip of coffee and every minute of post-work napping. Because here’s the thing: you are being and modeling the change that you wanted to see in the world.

You are an essential part of the journey for each one of those sweet (and sour) little buggars –those future business owners and leaders and decision-makers who will run the world while we slowly age and eventually retire (scary thought, I know, I know, so, let’s just bring this story back to the present tense). But in all seriousness, think about the self-improvement one inevitably makes throughout a normal lifetime. And now imagine that x10. That’s the experience of being a teacher. Indeed, as long as you are willing to reflect on how you can do better tomorrow, maintain a growth mindset and remain committed to practicing self-care, you will thrive. And you will have the journey of a lifetime.

I am currently on that journey. Although my teaching has transformed in the 6 years since I started teaching, I have only just begun the process of becoming the teacher that my students truly need me to be. In fact, it took me until this past fall to understand –to really understand—that teachers, including me, must move beyond lecture-style lessons. And yes, it still counts as lecturing if you have kids work with you in a small group to do their work. (I think of it this way: If I am the one explaining what should be done and why it makes sense, then I am teaching a lecture-style lesson). Now, why do we have to abandon our good-ol’ “sit 'n git” style of teaching, since it’s ostensibly worked for so long?

I think you already know the answer to that question. Students learn by tinkering, by exploring, by finding their words and sharing ideas. Even as adults, that is how we learn. And yet, in the name of efficiency and despite our own experiences to the contrary, so much of teaching takes place in the form of “you sit and copy my notes, listen to my rules, practice problems on your own, and then, hopefully, when you encounter a complex word problem, you will figure out how to do it right.”

In the name of full transparency, that was (more or less) the process of teaching that I used to follow. Sure, I tried to get students thinking by modeling my own thinking via “think-alouds” and prescriptive problem-solving strategy lists. But unsurprisingly, my students still just “didn’t get it.” They didn’t internalize any of my teaching! “Why aren’t they getting it?!” I would ask myself while pulling out my hair and blaming myself for being such an ineffective teacher; blaming them for being unable to make sense of it all in a meaningful or enduring way.

Upon reflection, it becomes so obvious to see: I didn’t get it. I didn’t understand that learning can only take place when students have multiple and varied opportunities to explore math on their own terms and in their own words. That means that my job, as the teacher, is to facilitate the intersection between what students can do, what they want to do, and what I can convince them to do!

I only just started to understand this distinction recently. What is amazing is that, since modifying my approach, my students have grown tremendously in their ability to communicate their mathematical thinking to me and to each other. This is because, for the last 4 months, I am been studying and practicing the art of mathematical reasoning with my students based on the book Routines for Reasoning by Grace Kelemanik, Amy Lucenta, and Susan Janssen Creighton. I have also been working with Dr. von Renesse on establishing a culture of bravery and peer-to-peer communication within the classroom.

Don’t the ideas of mathematical reasoning, bravery, and communication, sound so simple, so foundational, so…. implicitly interwoven into everything we do, anyway? And yet, If you are like me, you believe you incorporate these ideas into your classroom culture more than you actually do. After all, I’d thought I’d been doing mathematical reasoning for my previous 5 years of teaching.

But as I explored Routines for Reasoning and examined ideas with Dr. Renesse, I came to understand that I needed to improve the way I modeled ideas of mathematical thinking and bravery in front of my students. I needed to explicitly point out examples of courage in the classroom and draw attention to metacognitive strategies.

Put another way, I had to be brave and take the risk of trying new strategies that felt, at first, like a waste of precious time. I had to be courageous by overcoming the fear that my reluctant learners would refuse to engage in the new routines, that they might revolt or start throwing rotten fruit at me –never mind where they would have gotten rotten fruit.

Just as I would later teach my students to say, I first had to tell myself: “It’s okay to be wrong and to make mistakes along the way, because the process of being wrong teaches us more than if we had first been right.” It sounds kind of obvious. And yet, saying this phrase - repeating it over and over every chance I got, until my kids actually started believing it to have a sliver of truth– it felt radical. What I now understand, however, is that this radical little phrase has the power to change hearts and minds well beyond the boundaries of math. It is with this very phrase that I have fortified my students against math anxiety and promoted a culture of mathematical exploration. By celebrating mistakes and, yes, the inefficient process of growth, I saw even my most reluctant of students develop a better understanding of mathematical concepts. Thus, I can honestly report that what I really learned this semester was more than just some routines out of a book – it was the art of reasoning.

And now I want to support you in being brave and taking the risk of transforming your own classroom into a laboratory of mathematical thinking. To support you, I leave you a brief guide to implementing the 4 Routines for Reasoning along with teacher-ready lesson plans and tasks. While the routines can be modified for any grade level, I have left you tasks for major learning strands in grades 4 through 7.

Let me close by saying that I am so glad you are on this journey. I wish you, and the students whose lives you will touch throughout your career, the many joys of mathematical reasoning.

Routines for Reasoning Resources:

On this page, Liz provides an overview of the routines and makes some of her lesson plans available for others to use.